“Vezilier: a diplomat with a soldier’s face at the heart of an African conspiracy”

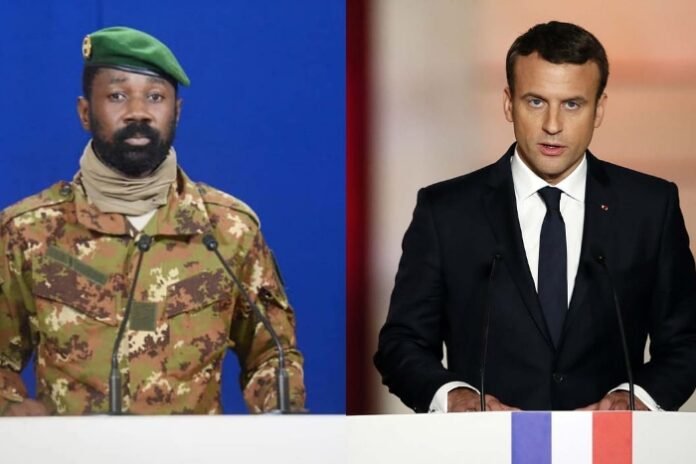

On August 15, 2025, the Malian authorities announced the arrest of several figures, including Lieutenant-Colonel Yann Christian Bernard Vezilier, an officer of the French Air Force and second secretary at the French Embassy in Bamako. Bamako accused him of taking part in a plot to overthrow the Malian authorities, making him a symbol of all the ambiguities surrounding the French presence in Africa.

From “Bob Denard” (the nom de guerre of Gilbert Bourgeaud) in the 1970s, who worked as a mercenary for France in Africa, to “Vezilier” today, the same logic emerges: France oscillates between influence, interference, and loss of control in the Sahel.

Colonel Vezilier: a diplomat-soldier in the eye of the storm

On August 15, 2025, the Malian authorities announced the arrest of several individuals accused of preparing a coup. Among them, a Frenchman: Yann Christian Bernard Vezilier, lieutenant-colonel in the French Air Force and second secretary at the French Embassy in Bamako.

Presented by Mali’s Minister of Security as “an agent linked to French intelligence,” Vezilier immediately became the center of a diplomatic standoff. Paris denounced “baseless accusations,” stressing that its officer enjoys diplomatic immunity under the Vienna Convention. Bamako, however, insisted: the “operation” had started on August 1, proof of a structured project aimed at destabilizing the transition.

Beyond the facts, one thing is clear: this arrest marks a new stage in the tug-of-war between France and Mali since the political rupture of 2022.

Bob Denard: the archetype of the French mercenary

To understand the symbolism of the “Vezilier affair,” one must go back to a name: Bob Denard. This former sailor turned mercenary, whose real name was Gilbert Bourgeaud, carried out operations for decades on behalf of France in Africa.

From Congo to Benin, and especially the Comoros, Denard embodied that parallel diplomacy in which mercenaries served as the armed wing of French interests, under the guise of protecting allied regimes or removing unruly leaders. His coups, often organized with the tacit blessing of the Élysée, remain remembered as the golden age of African mercenaries.

From Denard to Vezilier: continuity and rupture

The comparison between Denard and Vezilier is more than a journalistic shortcut: it highlights both continuity and transformation in French interference.

-

Continuity: the strategic objectives remain the same — control of resources (Nigerien uranium, Malian gold, Chadian oil), preservation of a sphere of influence against rivals, and prevention of overly independent regimes.

-

Rupture: while Denard operated as a mercenary, Vezilier acts in uniform at the very heart of the diplomatic apparatus. Yesterday’s “offshore” mercenaries have given way to an official confrontation between sovereign states.

The Sahel: battlefield of influence

Since 2020, the Sahel has entered a period of unprecedented turmoil. Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have all experienced military coups, often accompanied by virulently anti-French rhetoric.

The forced withdrawal of Operation Barkhane opened the door to other players: Russia, through Africa Corps (formerly Wagner), as well as Turkey, China, and the UAE. In this context, France seeks to maintain footholds in Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Chad.

But the growing number of accusations — such as those targeting Vezilier — underline a fact: the official discourse of counterterrorism is increasingly seen as a façade. For part of African public opinion, Paris remains associated with interference and the “manipulations” inherited from Françafrique.

Five key figures to understand the balance of power in the Sahel

-

Around 2,500 French soldiers remain deployed in West Africa after withdrawals from Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. The largest contingents are now in Abidjan (about 950 men), Chad (N’Djamena), as well as Senegal and Gabon.

-

Nigerien uranium, long vital to France’s nuclear industry, accounted for nearly 20% of EDF’s supply before 2023. Losing this strategic lever weakened Paris’s pursuit of energy independence.

-

The human cost of jihadism is colossal: according to ACLED, central Sahel (Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger) accounted for nearly 50% of global Islamist terrorism victims in 2024, with more than 20,000 deaths over five years.

-

In the wake of French withdrawal, Russia (Africa Corps, formerly Wagner) deployed several hundred men in Mali and Burkina Faso. Turkey provides drones and trainers, while the UAE and Qatar invest in bases and infrastructure.

-

These figures highlight a reality: the Sahel has become one of the world’s most contested regions. For France, the equation is simple but brutal — maintain a declining influence at growing political cost, or accept that the security center of gravity shifts to other powers.

Conclusion: Paris playing in the open

From Bob Denard to Yann Vezilier, France’s African story unfolds as a sequence of continuities and reinventions. The method evolves — from clandestine mercenary to diplomat-soldier — but the fundamental question remains: how far can a middle power go to defend its interests without assuming outright interference?

In this struggle, Paris now seems to be playing in the open. But every move it makes in the Sahel risks backfiring: the more the army takes over the role of the mercenaries, the more the legitimacy of the French presence erodes.