A Reading of Reda Addam’s Article on the Frenchification of Moroccan Education

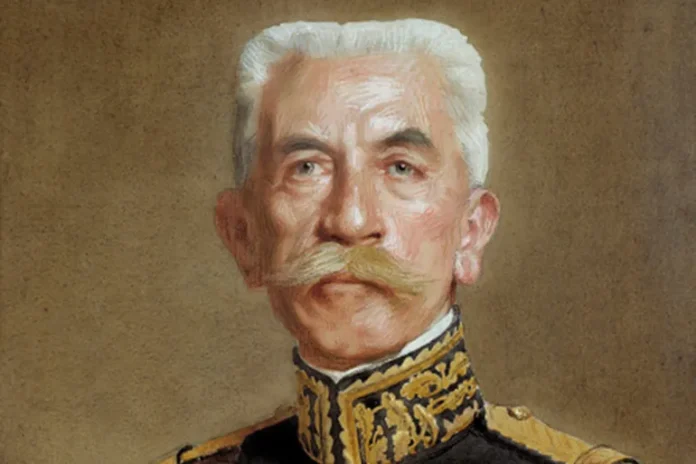

Since General Lyautey left Morocco, debate has continued around his legacy in administration, education, and culture. But for his name to resurface suddenly in 2025 through a provocative opinion piece titled “The Day Lyautey Decided to Frenchify Us” by journalist and geopolitical analyst Reda Addam — this cannot be seen as a mere historical echo, but rather a direct challenge to both memory and sovereignty.

Addam doesn’t merely raise the issue of education in French — he argues that it is a deliberate continuation of Lyautey’s cultural domination project, only this time enacted by Moroccan hands, from within Moroccan institutions.

So, is this a legitimate educational reform, or a subtle drift toward dependency? Can language be a neutral tool, or is it the gateway to identity and allegiance? This analytical reading tries to unpack these questions through three axes inspired by Addam’s article.

1. Lyautey Returns… Without Soldiers

When Lyautey, in the height of the French Protectorate, chose language — not guns — as his main tool of control, he knew that language subdues elites and disciplines educated classes more effectively than weapons.

Reda Addam reminds us that Frenchification was never just an educational policy, but a strategic instrument for producing obedient administrators and elites severed from their roots. And after independence, the colonial project wasn’t entirely dismantled — just repackaged.

Today, with the reintroduction of French in science and technical subjects, Addam warns of the danger of reproducing hegemony — this time, with Moroccan approval and no direct intervention from Paris.

Frenchification is no longer a colonial imposition, but a sovereign choice… against sovereignty.

2. Arabization: A Project That Was Never Given a Chance

Addam does not blame the Arabic language for failure, but rather the Moroccan state for not truly investing in the Arabization project. He highlights a lack of political will, poor planning, and the absence of scientific translation.

While it’s now trendy to declare that Arabization has failed, Addam poses an uncomfortable question:

“Did Arabization fail, or was it made to fail?”

How can a project succeed when students are taught in Arabic until high school, only to be thrown into higher education in French — a language they were never properly trained in? How can we trust Arabic in schools if we don’t Arabize the university, the civil service, or even official documents?

The result? A linguistically confused generation, fluent in neither the language of identity nor that of the market, losing trust in both their education — and themselves.

3. The New Frenchification: Sovereign Decision or Cultural Retreat?

Addam does not see today’s Frenchification as a reformist project but as a calculated retreat from the fight for cultural independence — a clear abandonment of Arabic as a language of science and knowledge.

He warns of an undeclared Frenchification, never discussed publicly, pushed forward by powerful francophone lobbies that see French as a class marker and a key to power.

In this process, Moroccan schools become factories for foreign loyalty rather than spaces for national identity-building.

It is a sovereign choice in form, but a genuine withdrawal from cultural emancipation.

Conclusion: What Kind of Modernity Do We Want?

Language is not merely a tool for education — it is an environment for knowledge, a framework for sovereignty, and a mirror of civilizational dignity.

The decision to Frenchify education cannot be divorced from this context — especially when it is made without national debate and without a strategic vision for linguistic and cognitive justice.

We are not against multilingualism — far from it. But it must occur within a national project that places Arabic in a position of strength, not marginalization, and makes openness a deliberate policy, not a soft surrender.

As Reda Addam rightly asks, we must ask again — louder this time:

“Do we want a truly national modernity rooted in our language and identity, or a francophone elitist modernity that replicates colonization — but this time with our own consent?”

The answer won’t come from ministry circulars, but from the collective conscience, state policies, and the kind of school we want for our children.